Lab: Representation Showdown

CAP-6640: Computational Understanding of Natural Language

Spencer Lyon

Prerequisites

L03.01: Sparse Representations (BoW, TF-IDF, Scikit-learn)

L03.02: Dense Representations (Word2Vec, GloVe, SpaCy, Gensim)

Outcomes

Apply TF-IDF and word embedding representations to a real text dataset

Compute and interpret document similarity using cosine similarity across representations

Explain how subword tokenization (BPE, WordPiece) handles out-of-vocabulary words

Compare sparse vs. dense representations on similarity and clustering tasks

Use sentence-transformers for document-level embeddings as a preview of modern methods

References

J&M Chapter 5: Embeddings (download)

HF Chapter 6: The Tokenizers Library (link)

spaCy Course Chapter 2: Word Vectors and Semantic Similarity

The Arena¶

We’ve spent the last two lectures building up two families of text representation. TF-IDF gives us sparse, high-dimensional vectors where each dimension is a vocabulary word. Word embeddings give us dense, compact vectors where dimensions encode learned semantic features. Both sides have passionate advocates.

But which one actually works better? The honest answer is it depends — and today we’ll see exactly what it depends on. We’ll load a real text dataset, build multiple representations, and pit them head-to-head on two tasks: finding similar documents and organizing documents into clusters. By the end, you’ll have the intuition to choose the right representation for a given problem.

Let’s set up the arena.

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.datasets import fetch_20newsgroups

from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import TfidfVectorizer

from sklearn.metrics.pairwise import cosine_similarity

from sklearn.manifold import TSNE

import spacy

import warnings

warnings.filterwarnings("ignore", category=FutureWarning)We’ll use the 20 Newsgroups dataset — a classic benchmark in NLP. It contains roughly 20,000 newsgroup posts across 20 topics. We’ll work with 4 categories that are nicely distinct:

# Load 4 categories from 20 Newsgroups

category_names = [

"rec.sport.baseball",

"sci.space",

"talk.politics.guns",

"comp.graphics",

]

newsgroups = fetch_20newsgroups(

subset="train",

categories=category_names,

remove=("headers", "footers", "quotes"), # strip metadata for fair comparison

random_state=42,

)

# Filter out very short documents (artifacts of header/footer removal)

min_length = 100

mask = [len(text) >= min_length for text in newsgroups.data]

texts = [text for text, keep in zip(newsgroups.data, mask) if keep]

targets = np.array([t for t, keep in zip(newsgroups.target, mask) if keep])

categories = [newsgroups.target_names[t] for t in targets]

short_categories = [c.split(".")[-1] for c in categories]

print(f"Documents after filtering: {len(texts)}")

print(f"\nCategory distribution:")

for cat in category_names:

short = cat.split(".")[-1]

count = sum(1 for c in categories if c == cat)

print(f" {short:12s}: {count}")Documents after filtering: 2088

Category distribution:

baseball : 505

space : 548

guns : 509

graphics : 526

Let’s peek at a sample document to see what we’re working with:

print(f"Category: {categories[0]}")

print(f"Length: {len(texts[0])} characters")

print(f"\n{texts[0][:500]}...")Category: talk.politics.guns

Length: 123 characters

What about guns with non-lethal bullets, like rubber or plastic bullets. Would

those work very well in stopping an attack?...

Building the Contenders¶

Contender 1: TF-IDF¶

Our first contender is the veteran — TF-IDF with Scikit-learn. We already know the drill from L03.01: fit a TfidfVectorizer, get a sparse matrix, and we’re ready to compute similarities.

tfidf_vec = TfidfVectorizer(max_features=5000, stop_words="english")

X_tfidf = tfidf_vec.fit_transform(texts)

print(f"TF-IDF matrix shape: {X_tfidf.shape}")

print(f"Non-zero entries: {X_tfidf.nnz:,} out of {X_tfidf.shape[0] * X_tfidf.shape[1]:,}")

print(f"Sparsity: {1 - X_tfidf.nnz / (X_tfidf.shape[0] * X_tfidf.shape[1]):.1%}")TF-IDF matrix shape: (2088, 5000)

Non-zero entries: 107,558 out of 10,440,000

Sparsity: 99.0%

Each document is now a 5,000-dimensional sparse vector. Over 95% of the entries are zero — most documents use only a small fraction of the vocabulary. But those non-zero entries carry meaningful signal about what each document is about.

Contender 2: Averaged Word Vectors¶

Our second contender uses dense representations. We’ll load SpaCy’s medium model (which includes 300-dimensional word vectors) and represent each document as the average of its token vectors.

Why averaging? It’s the simplest way to get from word-level vectors to a document-level vector: just take the mean across all tokens. SpaCy does this automatically — doc.vector returns the average of all token vectors in the document.

# Load SpaCy with only the components we need (vectors come from the vocab, not a component)

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_md", disable=["tagger", "parser", "ner", "attribute_ruler", "lemmatizer"])

# Process all documents — nlp.pipe() is much faster than calling nlp() in a loop

docs = list(nlp.pipe(texts, batch_size=50))

X_spacy = np.array([doc.vector for doc in docs])

print(f"SpaCy matrix shape: {X_spacy.shape}")

print(f"Non-zero entries: {np.count_nonzero(X_spacy):,} out of {X_spacy.size:,}")

print(f"Sparsity: {1 - np.count_nonzero(X_spacy) / X_spacy.size:.1%}")SpaCy matrix shape: (2088, 300)

Non-zero entries: 626,400 out of 626,400

Sparsity: 0.0%

Notice the contrast: the SpaCy matrix is 300-dimensional (vs. 5,000 for TF-IDF) and almost entirely non-zero. Dense and compact — that’s the whole point.

But averaging has a cost. A document about “space shuttle launches from Cape Canaveral” and a document about “my cat likes to launch itself off the couch into space” would both average out vectors for “space” and “launch” — even though they’re about completely different things. Context and word order are lost. How much does this matter in practice? That’s what we’re here to find out.

Subword Tokenization: Bridging the Vocabulary Gap¶

Before we bring in our third contender, let’s address a problem we flagged at the end of L03.02: out-of-vocabulary (OOV) words. Static embeddings like Word2Vec and GloVe have a fixed vocabulary. If a word wasn’t in the training data — a misspelling, a technical term, a new slang word — it simply has no vector.

Subword tokenization solves this by breaking words into smaller pieces. Instead of treating “transformerification” as a single unknown token, a subword tokenizer splits it into recognizable parts like “transform”, “er”, “ification”. The model can then compose a meaning from the parts.

The two most important subword algorithms are:

BPE (Byte Pair Encoding): starts with individual characters, iteratively merges the most frequent adjacent pairs. Used by GPT-2, GPT-3/4, LLaMA.

WordPiece: similar to BPE but selects merges that maximize the likelihood of the training data. Used by BERT.

Let’s see them in action:

from transformers import AutoTokenizer

# Load a BPE tokenizer (GPT-2)

bpe_tok = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("gpt2")

# Load a WordPiece tokenizer (BERT)

wp_tok = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("bert-base-uncased")

# Test on a mix of common and unusual words

test_words = [

"hello",

"unbelievable",

"transformerification",

"NLP",

"spaCy",

"antidisestablishmentarianism",

"asdfjkl",

]

print(f"{'Word':<30} {'BPE Tokens':<40} {'WordPiece Tokens'}")

print("-" * 100)

for word in test_words:

bpe_tokens = bpe_tok.tokenize(word)

wp_tokens = wp_tok.tokenize(word)

print(f"{word:<30} {str(bpe_tokens):<40} {str(wp_tokens)}")Word BPE Tokens WordPiece Tokens

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

hello ['hello'] ['hello']

unbelievable ['un', 'bel', 'iev', 'able'] ['unbelievable']

transformerification ['trans', 'former', 'ification'] ['transform', '##eri', '##fication']

NLP ['N', 'LP'] ['nl', '##p']

spaCy ['sp', 'a', 'Cy'] ['spa', '##cy']

antidisestablishmentarianism ['ant', 'idis', 'establishment', 'arian', 'ism'] ['anti', '##dis', '##est', '##ab', '##lish', '##ment', '##arian', '##ism']

asdfjkl ['as', 'df', 'j', 'kl'] ['as', '##df', '##jk', '##l']

Notice the patterns:

Common words (“hello”) stay intact in both tokenizers

Compositional words (“unbelievable”) get split into meaningful parts

Rare/invented words (“transformerification”, “asdfjkl”) get broken into smaller pieces — but they still get some representation, unlike static embeddings which would return nothing

The

##prefix in WordPiece (andĠin BPE) marks whether a token is a word start or a continuation

This is why modern transformer models rarely suffer from OOV problems — their tokenizers can handle essentially any string of text. We’ll see these tokenizers again when we work with BERT and GPT in Weeks 6–7.

Contender 3: Sentence-Transformers¶

We have one more contender — and it’s a preview of where we’re headed later in the course. Sentence-transformers are transformer-based models specifically trained to produce high-quality sentence and document embeddings. Unlike our SpaCy approach (which just averages word vectors), these models are trained end-to-end to make similar documents produce similar vectors.

We’ll use the all-MiniLM-L6-v2 model, which is small and fast but produces surprisingly good embeddings.

from sentence_transformers import SentenceTransformer

st_model = SentenceTransformer("all-MiniLM-L6-v2")

X_st = st_model.encode(texts, show_progress_bar=True, batch_size=64)

print(f"Sentence-transformer matrix shape: {X_st.shape}")Warning: You are sending unauthenticated requests to the HF Hub. Please set a HF_TOKEN to enable higher rate limits and faster downloads.

BertModel LOAD REPORT from: sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L6-v2

Key | Status | |

------------------------+------------+--+-

embeddings.position_ids | UNEXPECTED | |

Notes:

- UNEXPECTED :can be ignored when loading from different task/architecture; not ok if you expect identical arch.

Sentence-transformer matrix shape: (2088, 384)

We now have three contenders ready to compete:

| Contender | Dimensions | Type | Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| TF-IDF | 5,000 | Sparse | Count word importance |

| SpaCy Avg. Vectors | 300 | Dense | Average pre-trained word vectors |

| Sentence-Transformers | 384 | Dense | End-to-end trained document encoder |

Let the showdown begin.

Round 1: Nearest Neighbors¶

The first test: given a query document, which representation does the best job finding similar documents? We’ll pick a document, find its 5 nearest neighbors under each representation, and compare.

# Pick a space-related document as our query

space_indices = [i for i, c in enumerate(categories) if c == "sci.space"]

query_idx = space_indices[0]

print(f"Query document (category: {short_categories[query_idx]})")

print(f"{texts[query_idx][:300]}...")Query document (category: space)

Actually, the "ether" stuff sounded a fair bit like a bizzare,

qualitative corruption of general relativity. nothing to do with

the old-fashioned, ether, though. maybe somebody could loan him

a GR text at a low level.

didn't get much further than that, tho.... whew.

...

Now let’s find the nearest neighbors under each representation:

# Compute similarities to the query document

tfidf_sims = cosine_similarity(X_tfidf[query_idx], X_tfidf).flatten()

spacy_sims = cosine_similarity(X_spacy[query_idx].reshape(1, -1), X_spacy).flatten()

st_sims = cosine_similarity(X_st[query_idx].reshape(1, -1), X_st).flatten()

# Get top 5 (excluding self)

def top_k_neighbors(sims, k=5):

indices = np.argsort(sims)[::-1]

# Skip self (similarity = 1.0)

return [(idx, sims[idx]) for idx in indices if idx != query_idx][:k]

tfidf_top5 = top_k_neighbors(tfidf_sims)

spacy_top5 = top_k_neighbors(spacy_sims)

st_top5 = top_k_neighbors(st_sims)

# Display side by side

print(f"{'TF-IDF':<35} {'SpaCy Avg Vectors':<35} {'Sentence-Transformers'}")

print("-" * 105)

for i in range(5):

t_idx, t_sim = tfidf_top5[i]

s_idx, s_sim = spacy_top5[i]

st_idx, st_sim = st_top5[i]

print(

f"[{short_categories[t_idx]:>10}] {t_sim:.3f} "

f"[{short_categories[s_idx]:>10}] {s_sim:.3f} "

f"[{short_categories[st_idx]:>10}] {st_sim:.3f}"

)TF-IDF SpaCy Avg Vectors Sentence-Transformers

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[ space] 0.340 [ baseball] 0.988 [ space] 0.588

[ guns] 0.116 [ baseball] 0.987 [ space] 0.377

[ graphics] 0.113 [ baseball] 0.987 [ space] 0.370

[ space] 0.095 [ graphics] 0.987 [ space] 0.365

[ graphics] 0.094 [ baseball] 0.986 [ space] 0.363

Look at the category labels for each column. Are all three representations finding neighbors from the correct category (sci.space)? Or are some representations getting confused, pulling in documents from unrelated topics?

TF-IDF tends to do well here because it matches on specific vocabulary — space-related documents share rare technical terms like “orbit”, “NASA”, “shuttle”. Averaged word vectors can sometimes get confused because averaging washes out specificity. Sentence-transformers typically perform well because they’re trained specifically for semantic similarity.

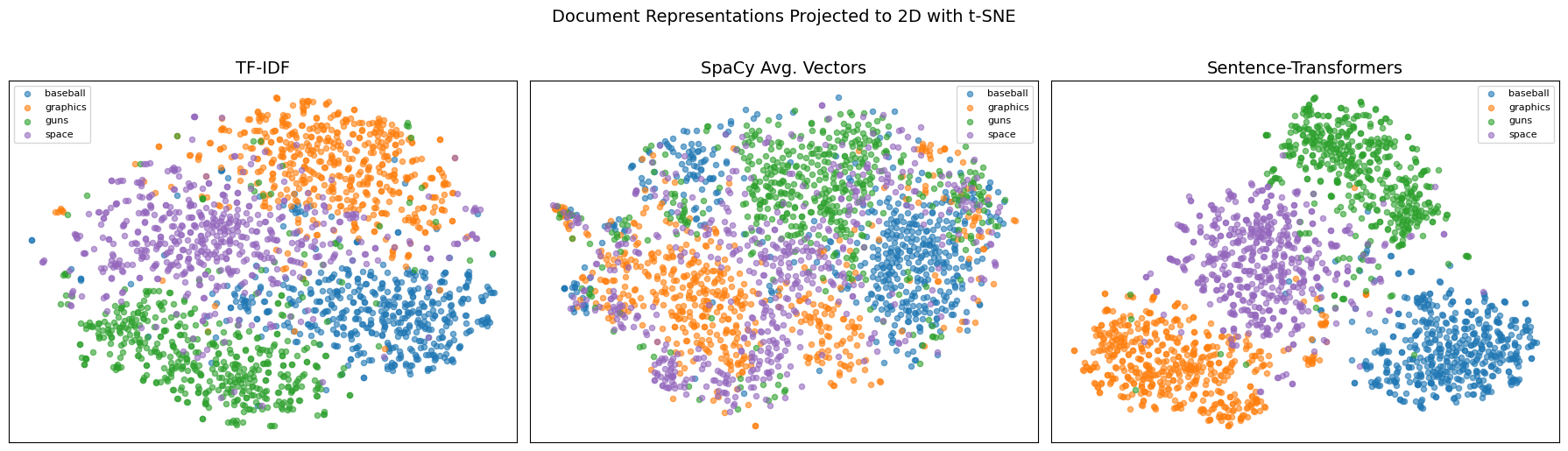

Round 2: Cluster Visualization¶

Nearest neighbors tell us about individual queries. But we want the big picture: how does each representation organize the entire dataset? Are documents from the same category clustered together? Are the categories well-separated?

We’ll use t-SNE (t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding) to project each representation down to 2 dimensions for visualization. t-SNE tries to preserve local neighborhood structure — points that are close in the high-dimensional space should stay close in 2D.

# Apply t-SNE to each representation

tsne_params = dict(n_components=2, random_state=42, perplexity=30)

X_tfidf_2d = TSNE(**tsne_params).fit_transform(X_tfidf.toarray())

X_spacy_2d = TSNE(**tsne_params).fit_transform(X_spacy)

X_st_2d = TSNE(**tsne_params).fit_transform(X_st)

# Plot all three side by side

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 3, figsize=(18, 5))

unique_cats = sorted(set(short_categories))

colors = plt.cm.tab10(np.linspace(0, 0.4, len(unique_cats)))

for ax, X_2d, title in zip(

axes,

[X_tfidf_2d, X_spacy_2d, X_st_2d],

["TF-IDF", "SpaCy Avg. Vectors", "Sentence-Transformers"],

):

for color, cat in zip(colors, unique_cats):

mask = np.array([c == cat for c in short_categories])

ax.scatter(X_2d[mask, 0], X_2d[mask, 1], c=[color], label=cat, alpha=0.6, s=20)

ax.set_title(title, fontsize=14)

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_yticks([])

ax.legend(fontsize=8, loc="best")

plt.suptitle("Document Representations Projected to 2D with t-SNE", fontsize=14, y=1.02)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

This visualization is revealing. Compare the three plots:

TF-IDF typically produces reasonably distinct clusters because topics use different vocabularies. Space documents talk about “orbit” and “NASA”; baseball documents talk about “pitcher” and “batting”. The lexical signal is strong.

SpaCy averaged vectors may show more overlap between clusters. Averaging many word vectors together tends to push all documents toward a “generic text” center, reducing the distinctiveness of each topic.

Sentence-transformers often produce the tightest, most separated clusters because the model was trained specifically to place semantically similar texts close together.

The pattern isn’t always this clean — t-SNE is stochastic and sensitive to its parameters. But the general trend is consistent: representations that encode more semantic information produce better-organized embedding spaces.

The Verdict¶

We’ve now seen three representations compete on real data. Let’s summarize what we’ve learned about when each shines:

| TF-IDF | SpaCy Avg. Vectors | Sentence-Transformers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strengths | Fast, interpretable, good lexical matching | Captures synonymy, compact | Best semantic similarity, handles paraphrases |

| Weaknesses | No synonymy, high-dimensional | Averaging loses specificity | Slower, requires GPU for large-scale use |

| Best for | Keyword search, topic classification | Quick semantic baseline | Semantic search, clustering, retrieval |

| Setup cost | Minimal (sklearn only) | Medium (SpaCy model download) | Higher (transformer model download) |

The key insight is that there’s no universally best representation. TF-IDF is still a strong baseline for tasks where lexical overlap matters — and it’s orders of magnitude faster to compute than transformer-based embeddings. But when you need to understand that “the spacecraft launched successfully” and “the rocket took off without issues” are about the same thing, you need dense representations.

And within dense representations, the gap between averaged word vectors and purpose-built sentence encoders is significant. Averaging is a crude operation that discards word order and dilutes meaning. Sentence-transformers are trained end-to-end to produce high-quality document embeddings — and it shows.

Wrap-Up¶

Key Takeaways¶

What’s Next¶

In Week 4, we’ll put these representations to work on a core NLP task: text classification. We’ll train classifiers — Naive Bayes, SVM, Logistic Regression — on top of the feature representations we’ve built here. You’ll see that the choice of representation has a direct impact on classification accuracy. We’ll also explore sequence labeling tasks like named entity recognition, where the order of words that our bag-of-words models discard becomes essential.